Prion diseases

by Kevin Barretto, Omar Merdan, Michelle Potestio, and Vivian Salib

Product 1: video

Product 2: blog post

In the past few decades, human life expectancy has increased considerably. Advances in agriculture, industrialization, and medicine have contributed to adding years to the average life span of those in developed countries. Just in the past one hundred years, medical technologies alone have made a huge impact. Through our understanding of immunology and infection, we have created vaccines that have helped to eliminate the incidence of once deadly diseases and epidemics. Advances in surgery and medications have allowed us to treat illness and trauma that were once considered fatal. Thanks to this progress, it is now fairly common for many people to live to old age. However, the aging population now faces a new threat; one that science is only beginning to understand.

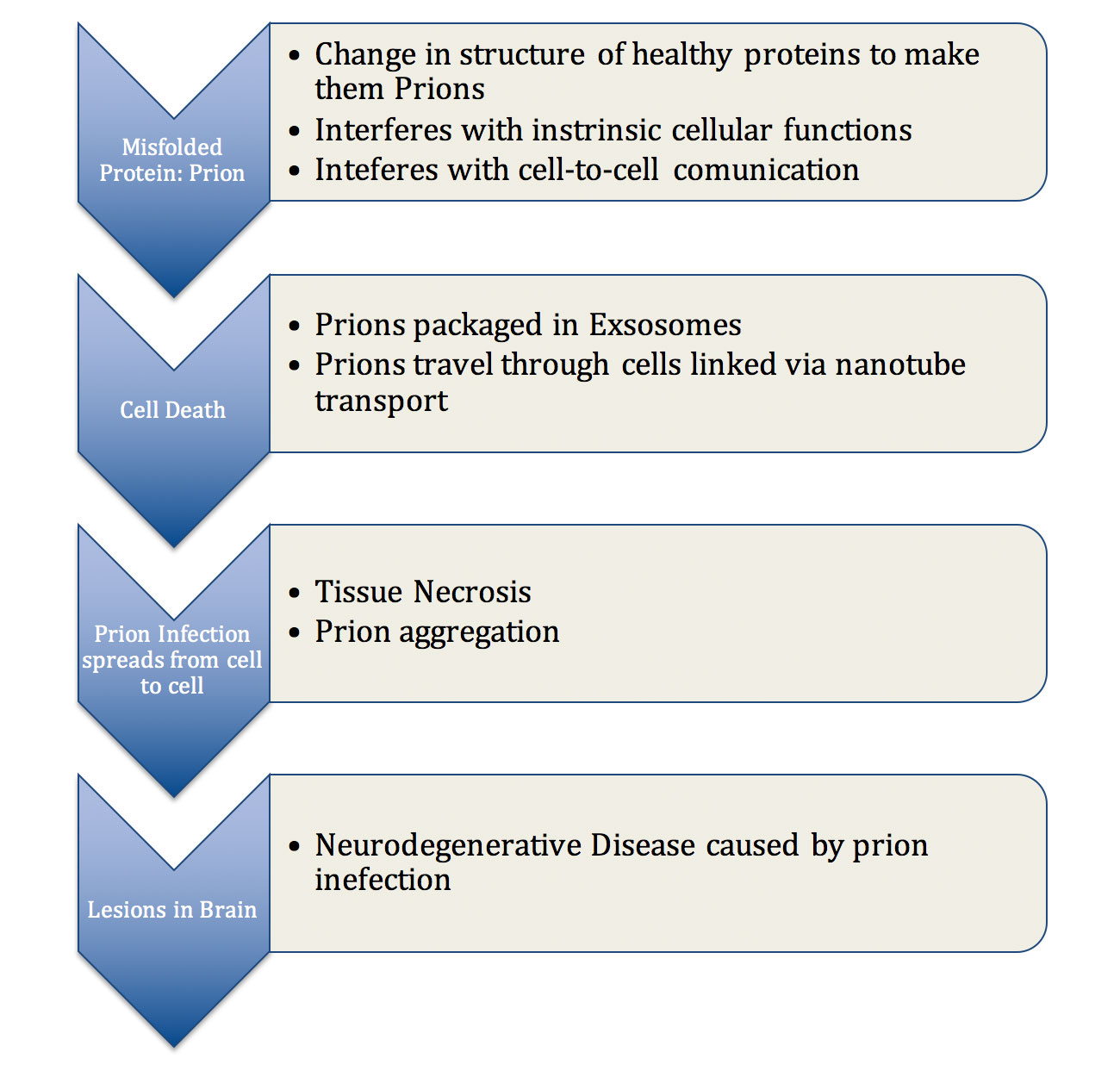

Old age is one of the strongest risk factors for neurodegenerative diseases. Recent evidence has linked the root cause of most neurodegenerative disease to a poorly understood infectious agent known as a prion. Unlike other infectious agents – such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi – prions do not contain any DNA. They are composed of proteins, which come in many different shapes and sizes. Normal protein structure is determined by the way in which the protein undergoes folding in order to assume its final shape. Prions have been misfolded, resulting in a change in both structure and function. Prions are remarkably interesting in their ability to increase their numbers by interacting with “healthy” or normal proteins. Through this interaction, they change the shape of the healthy proteins, thus converting them into the prion state. The new prion can then go on to infect other healthy proteins, starting a chain reaction that leads to a buildup of prions. The ability to transmit their disease to other cells is often compared to that of a viral infection. In fact, there are even different prion strains, based on varying types of misfoldings, which are classified in a similar way to viral strains. However, the mechanism by which prions inflict damage is far from similar to other infectious agents and is currently not well understood.

Some prion diseases are genetic, while others are acquired. The fact that age plays such a key role in susceptibility brings in the question of whether the body loses its ability to identify and get rid of misfolded proteins. Alone, a single prion does not pose a major threat to the well-being of a cell. However, its fast replicating ability causes prions to grow in number and start to clump together, forming large mobile prion clusters. These clusters of misfolded proteins interfere with normal cellular functions and cell-to-cell communication, which results in the neurodegenerative nature of prion diseases.

Prions contradict our normal understanding of infectious agents, which rely on the instruction of DNA to self-replicate. Traditional infections have been treated by our understanding of the immune system, which has allowed us to aid our body’s natural ability to ward off attack. However, prions seem to fly under the radar and remain undetected by the body’s defenses when spreading from cell to cell. They accomplish this by using what some scientists refer to as a “Trojan horse” delivery system. Prion clusters are often accidently packaged by cells into structures known as exosomes, small vesicles that carry various biological materials between cells. Exosomes can be thought of as delivery boxes. Once the prion cluster is put in the box, it leaves the infected cell and finds its way to new healthy cells. Once the vesicle enters the new cell, the toxic prions are released into the cell body. Prions also take advantage of cells linked by membrane nanotubes, which connect the contents of cells to allow for easy exchange of molecular cargo. Nerve cells commonly contain membrane nanotubes, which make them especially susceptible to prion infection that takes advantage of these cellular bridges. As seen in figure 1, these primary methods of spreading allow prions to self-propagate and infect cells, tissues, and eventually entire organ systems controlled by the brain with virtually no resistance.

Figure 1: Pathogenesis of prion related disease, describing the steps which explain how prions are capable of disrupting cellular function and spreading inside a cell, in between cells, and subsequently throughout the brain tissue.

Figure 1: Pathogenesis of prion related disease, describing the steps which explain how prions are capable of disrupting cellular function and spreading inside a cell, in between cells, and subsequently throughout the brain tissue.

With the aging population constantly growing, neurodegenerative diseases are expected to reach an extremely high rate of prevalence in the coming decades. According to experts in this field, our current lack of knowledge of prion phenomena is an indicator that more work must be done in this field if we are to address the prominent diseases that will affect our future. There are still many unanswered questions as to how initial transmission of prion infection occurs and how one prion can generate clusters that lead to toxicity in the cell. It is also not clearly understood what role age plays and why it seems to be a common risk factor for protein misfolding diseases. The current method of detecting prions in the body is insensitive and not very accurate. Also, the risk of contamination outbreaks is still a looming threat as prions are resistant to conventional methods of sterilization. However, there is still hope that future advances in biomedical research and new imaging technology to study the subcellular world will allow us to understand the mechanism of the disease. This will subsequently lead to the development of new therapies.

Product 3: podcast

References:

- Aguzzi, Adriano, and Asvin K.K. Lakkaraju. “Cell Biology of Prions and Prionoids: A Status Report.” Trends in Cell Biology (2015): S0962-8924(15)00158-0. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.08.007